So to my mind, while "Dad" as a word originated in around 1500, it was an evolution of whatever previous word they had been using for the same concept. The modern reader would think, perhaps, that the speaker was talking about the fourth note after Do-Re-Mi. If we had a character in a medieval dialogue tenderly calling their father "Fa" it might have been historically accurate - but it would be gibberish to modern readers. So maybe the young kids would call their male parent "Pa" or "Pa Pa" in the babbling style that most babies have. But would all children in medieval times only ever call their male parent by the official title of "Fader"? Was there never an opportunity for a child to use a more gentle version of a word when they were feeling affectionate? Maybe "Fa"? The Latin word was "Pater". We have already changed that by turning it into "father". In Middle English, there was a word, "fader", meaning the male parent of a child. So how do we find a healthy middle ground where the characters are using words that clearly convey the tone of what is being said, without appearing to be hanging out in a suburban mall chewing bubble-gum? So we can probably also agree that, since we can react to new-slang even in modern interactions, too-current slang would feel improper in a novel with historical characters. If someone came up to us and said "My bad, Pops, that skate is too leet!" many of us might form an opinion of the speaker because they were using slang and not "proper English." If we imagine this discussion going on at a job interview for a bank finance officer, in many cases the dialect style might affect the hiring decision. The interesting thing is that we react to phrasing and word use in our every day life. These would be choices of word or phrasing. So now let's look at things which are not physical anachronisms. Certainly a person in middle ages shouldn't be talking about "faster than an airplane" or "sharper than a rapier" since those things did not yet exist. So let's look at the other side of the scale - using words that are too modern.įirst, let's agree that physical anachronisms should never enter into dialogue (or into descriptions either, for that matter). So we accept, on one hand, that we need to create dialogue using modern definitions that modern readers will understand. That last line in essence says "And Saluces, this noble country was called." But would a modern reader know that? Is it reasonable to expect them to? In the middle ages, the word "highte" referred to the name of something. If we used the word "Gay" in a modern novel - no matter what it might have meant in medieval ages - we have to be aware of how our modern readers will perceive it, including its shadings of meaning. Words change over the years, both in the way they're spelled and the way they're used.

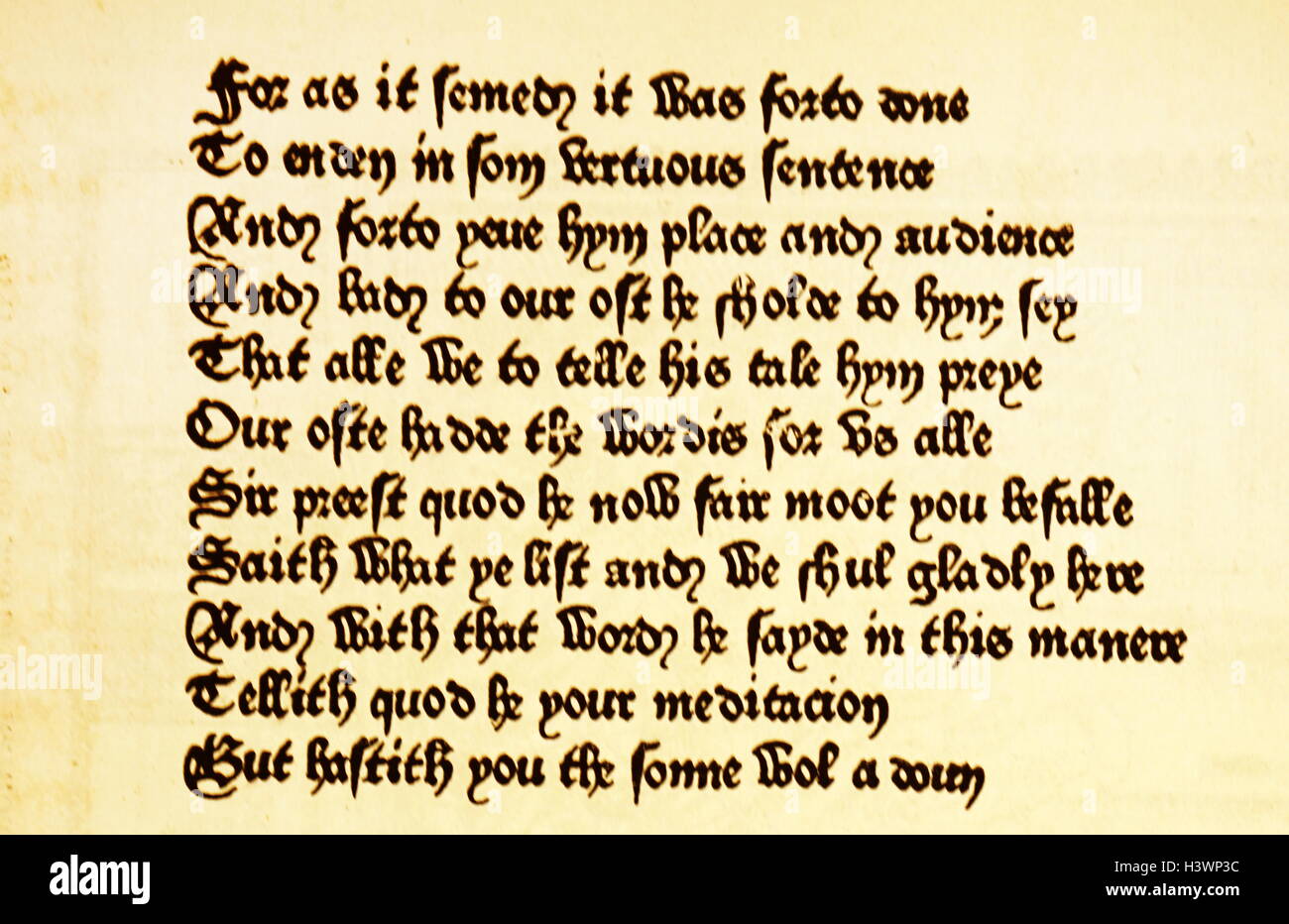

Maybe we might figure out that "tour" was an alternate spelling of "tower".īut would we know that "highte" meant, not a measurement of how tall something was, but rather that a name was associated with something? We get the sense that "toun" is now "town" and "fadres" is now "fathers". Most of us can understand that first line - that something exists on the west side of Ytaille, i.e. That founded were in tyme of fadres olde,Ĭertainly in some cases the words are the same, even if the spellings have altered over the years. Where many a tour and toun thou mayst biholde The language reads like this (the "typos" are correct):

If we look at The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, written in the 1300s, it is in Middle English. Certainly most readers would be completely lost if the novel was written in Middle English! One of the most challenging aspects of writing a medieval novel is to create authentic sounding medieval dialogue that the reader can follow.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)